“A ticking time bomb.” “The silver tsunami.” People know by now that the world’s population is aging. And most media convey this information as a warning of impending doom. While marketers and economists talk about the “longevity economy” and its potential profits, most companies have been slow to catch on. The Longevity Economy* explains trends driving this market and helps readers shift their thinking.

The Longevity Economy: Unlocking the World’s Fastest-Growing, Most Misunderstood Market,* is a 2017 book by Joseph F. Coughlin, Founder and Director of the MIT AgeLab. It summarizes his more than two decades of work and gives businesses a framework to understand the needs of older consumers. Thus help them make products that, in Couglin’s words, “excite and delight” older adults. In other words, the book teaches you how to change your mindset about old age so you can cash in on the longevity economy.

Roots of the old age narrative

Terms like “silver tsunami” connote images of frail elderly people overwhelming our healthcare system and bankrupting Social Security. Or alternatively, of healthy seniors who refuse to cede political power, wealth or status to the next generation. Even as they spend most of their time taking expensive vacations or living it up on the golf course.

The roots of this narrative lie in the 19th century when early medical knowledge held that “vital energy” declined as a person grew older. This belief combined with the 20th-century obsession with industrial efficiency. The prevailing societal view was that the aged were inherently less healthy than younger people and uniformly incapable of economic production.

Old narrative’s climax

Enter brilliant marketers and real estate developers, who recognized an opportunity among retirees whose pensions and Social Security afforded them a comfortable lifestyle. Especially if they moved to a place where real estate was cheap. Thus began the first US retirement community in 1960, Sun City.

Famous retirement communities include Sun City in Arizona, The Villages in Florida, and Leisure World (now called Laguna Woods) in Southern California. They aim to make older adults’ lives free of maintenance and full of recreational and social activities. They usually offer amenities like on-site dining and healthcare that provide convenience as well as peace of mind for emergencies.

The Golden Years

People who bought into these retirement communities built a concept of “retirement” as a whole new phase of life. In the past, you worked until you were no longer able to perform your job, were forced out by your employer, or you died. Now you retired from work to pursue a life of leisure. A life filled with golf, new friends and social commitments that might keep you busier than you were in your past work life.

My mother-in-law used to live in Laguna Woods. For her, it was a fantastic option. She sold her home of 40+ years and moved into a three-bedroom condo with a view over expansive manicured grounds. She made friends at the hot tub, onsite Bible studies and social center activities. For her, it was perfect.

Not universally golden

But not everyone wants to move to a place that’s restricted to residents 55 and older. In fact, 90% of us don’t want to move at all, according to an AARP study.

Add to that financial worries. Increasing longevity makes people anxious that they may run out of money to pay (often steep) monthly service fees. In the worst case, they’d have to move out of their retirement home late in life. In other words, the good times would come to an abrupt halt.

Trends driving a new narrative of old age

Several trends are converging to make the old narrative obsolete.

Longevity

Across the world, people are living longer. Not only are infant mortality down and lifespans longer. Birthrates have declined, even in developing countries. Many countries across the globe experienced their own baby boom after World War II, and those babies are now becoming grandparents and even great-grandparents.

As of 2015, there are 617 million people ages 65+ in the world. This will grow to 1 billion by 2030, and 1.6 billion by 2050.

As quoted in the book, worldwide older adult spending is forecast to reach $15 trillion by 2020. In the US alone, consumers aged 50+ control 83% of household wealth.

Technology

Not only are people living longer, but technology is enhancing everyone’s life. To date, technological advances for older adults have focused largely on health and safety issues. Things like automated medication reminders.

Going forward, we’ll harness technology not only to attend to older adults’ needs (think: care robot), but also to address their wants (think: self-driving car).

Technology has accelerated the pace of change in the world over the past decades. We can barely imagine what lies in store to enhance the lives of older (and younger) people in coming years.

Baby boomers

Demographers, marketers, economists, and politicians have learned never to underestimate the boomer generation. Baby boomers started turning 65 in 2011 and will continue to do so through 2030. As they grow older, the world will change to accommodate them.

They’ve been changing the world since they were youth protesting the Vietnam War. They’ve agitated for women’s rights, gay rights, the right to choose as well as the right to life. They’re such a large demographic cohort that companies must respond to their preferences.

In short, boomers are accustomed to a world that adapts to serve their needs and wants. They aren’t going to give up this mindset as they grow older. In fact, many boomers hesitate to acknowledge that in fact, they are growing older.

Companies face an enormous baby boomer market they won’t be able to serve unless they change. Boomer customers don’t accept the notion that old age is a time of greed (i.e., pursuing leisure and not contributing to society) and need (becoming sick and frail).

To succeed in the longevity economy, business has to change its perspective on old age.

Women

Women’s significance in changing attitudes toward aging cannot be missed. Not only are more women working and earning their own incomes than in the past. Women also continue to provide the bulk of elder care – at times caring for both their parents and their children. Of note, females influence 64% of consumer purchase decisions in the US.

As Coughlin states, “The future is female.” Companies who succeed in the longevity economy will employ female workers, listen to female consumers, and work with female entrepreneurs.

It’s time to rewrite the old age narrative

The Longevity Economy’s main point is simple: it’s time for a change.

Positive elements

Some good things came from the 20th-century view of old age. FDR signed the Social Security Act into law in 1935. At first, it applied to only 60% of the American workforce. But later it extended to serve nearly everyone, a kind of national pension plan. Congress passed the Older Americans Act in 1965 in response to policymaker concerns about a lack of community services for older people. And Johnson signed the Medicare bill that same year, thus providing national healthcare for all older Americans.

But it’s holding us back

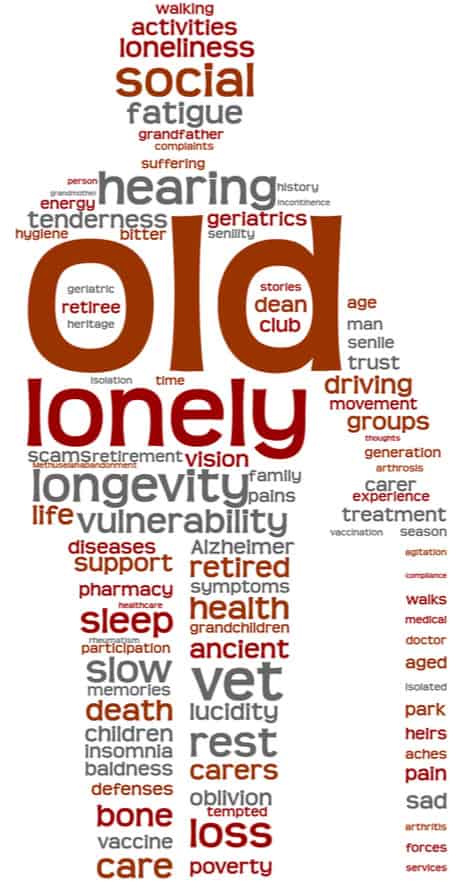

The old narrative’s portrayal of older people as “needy and greedy” has led companies to focus products for this segment on health and safety issues. We’ve seen the clunky cell phones and adult diapers. As well as the Personal Emergency Alert Systems (PERS) – those alarms that people don’t want to wear around their necks.

True innovation requires more than designing products that are easy to use and address a safety concern. The best products for older adults will, according to Couglin, “excite and delight” them. No one wants to buy a device that labels her as old or infirm. The sooner companies understand this fact, the more they stand to win in the longevity economy.

Product examples

The author gives lots of examples to illustrate how companies and individuals are changing the old age narrative.

Universal design, transcendent design

The OXO line of cookware and kitchen gadgetry is an example of products originally designed for older adults, but which quickly attracted a broader customer base. Sam Farber (of “Farberware” fame) had an idea for comfortable cookware when his wife’s arthritis prohibited her from using a traditional potato peeler. Although retired, he teamed with a crack designer, Patty Moore, to create a successful line of products that appeal to all ages, not just older people.

Coughlin calls products like the OXO potato peeler “transcendent design.” Transcendent design is universal design taken to the next level. To make his point, he compares OXO’s ergonomic potato peeler to a lever-style door handle. Both are universally-designed products – both make a task easier for you regardless of your age.

But, as the author puts it:

Unless it becomes absolutely necessary, switching doorknobs to handles isn’t the kind of thing that gets people off the couch, into their car, and off to Home Depot. Door handles are great . . . But no one covets them. . . .

But when someone accustomed to a slippery, wooden, cylindrical potato peeler tries their friend’s ergonomic peeler, they stop and say to themselves, I want that.

Retirement village to virtual village

The chapter, “A Tale of Two Villages,” illustrates the changing narrative of age by contrasting The Villages with Beacon Hill Village. The Villages is a retirement community of more than 50K residents ages 55+ in XX, Florida. It was created by a real estate developer to sell to older adults. It offers the kind of easy living described above as the golden years.

Beacon Hill Village, in contrast, was developed by residents of Beacon Hill, a historic and affluent neighborhood of Boston. They banded together to form a club, which later became its own 501(c)3 organization. The purpose of the association was to help older residents with needs for transportation, property maintenance, household tasks and so on.

Since this first virtual village formed in 1999, over 350 such villages have launched or are in development across 45 states. They assist older adults who want to stay in their homes and communities. They preserve your independence by offering services or referrals that address needs you may have as you age. Many of them also provide social gatherings and centrally organized activities.

Product hacks

Coughlin talks about product “hacks” that illustrate the creativity of older adults in finding new uses for existing things. In particular, for technologies that engineers may have designed with a different demographic in mind.

For example, the author shows how an 81-year-old professional maintains her independence and standard of living in retirement by:

- Renting out her spare bedroom with Airbnb

- Using delivery services for groceries, medications, restaurant meals and more

- Folding laundry, changing lightbulbs and so on as needed with TaskRabbit

- Summoning Uber for rides

Not only does she prefer to live in her community. The total cost of these auxiliary services falls well below a typical service fee at a retirement community in her area.

In another example, he discusses Stitch, a company which bills itself as “the world’s only companionship community created for members, by members.” He tells the story of a woman who, after a “grey divorce,” at first joined dating sites because she thought that’s how she’d find a companion.

But she realized she wasn’t looking for a boyfriend. She just wanted to find people who shared her love of music and would attend concerts and cabarets with her. So she used Stitch to find other women who had this interest in common with her. Stich is only for people over 50, and it boasts over 20,000 active members.

It’s not a dating site, but it works like a dating site. You could call it a dating site hack.

Longevity Explorers

Although not mentioned in the book, a group to watch and maybe join is the Longevity Explorers. This concept started with a club of older adults in San Francisco, but it’s spreading across the country.

Longevity Explorers evaluate existing products, share ideas on new products they’ve come across, and now are doing some “sponsored explorations” in conjunction with companies who want to design for older adults.

There’s a great interview with Richard Caro, a founder of the Tech-Enhanced Life and Longevity Explorers, on the podcast by Leslie Kernisan, Better Health While Aging. This podcast offers insights on topics relating to older adult health. Dr. Kernisan discusses a range of geriatric issues, but she has a special interest in technology as it relates to older adults. The interview with Caro includes a funny segment on Amazon’s smart speaker, Alexa. This is a product I recently blogged about in relation to how it can help you age in place.

New narrative characteristics

The new narrative of old age is still developing. But characteristics of modern older adult consumers are clear:

- They don’t want the sole focus of new products to be health and safety

- They are insulted by dumbed-down products

- Products must not frustrate older consumers

- Packaging should be easy to open

- Instructions should be clear and devices simple to operate

- Colors have to be distinguishable by aging eyes (over time the eye becomes more and more opaque to blue light, so it’s hard to distinguish some colors)

- They won’t buy boring stuff!

AGNES

Colleagues at the MIT AgeLab invented AGNES (Age Gain Now Empathy System), a suit you can put on to approximate physical issues you might have as an older person. They work with CEOs, designers and marketers. Product teams don AGNES outfits and experience products as an older consumer might.

More than anything, the AGNES suit has led product designers to experience an emotional connection with their older consumer. They learn to feel what it’s like to look at store shelves with restricted vision. To deal with mobility challenges as they try to get in and out of a car, or to operate a vehicle with slower reaction times than they used to have.

AGNES-based insights have led to innovative approaches to store design at CVS, like placing heavier objects higher up so consumers don’t have to bend down to pick them up and put them in the cart. They’ve also resulted in dashboard changes in BMWs – including the originally hated but now widely imitated iDrive system.

Challenges

Changing the narrative of old age will not come about easily. For one thing, multiple generations have grown up with an attitude that work is primarily for people ages 18-65. That after 65, you “deserve” to pursue leisure and/or you become too infirm to do anything other than drain Medicare and Social Security of their shrinking resources.

People in midlife are confused

In fact, people in their 50s and 60s who are approaching “official” retirement age feel confused about what they want to do with the rest of their lives. Which could last another 30 or more years. They want to continue to live with purpose and wake up energized to make a difference in the world. Many aren’t sure when or if they want to stop working.

Tech is a young man’s domain

Even though technology is a key element driving mindset change, a new narrative about the importance of older adults as makers and consumers is particularly challenging in Silicon Valley and other tech-oriented cities. Young males dominate tech companies across the globe.

As Coughlin cites, the ten largest companies in Silicon Valley are 70% male. Only 3% of venture-backed companies have female CEOs. Not only are tech companies largely male, but they also are young. Amazon and Google’s median ages are 30, and Facebook’s is 29.

But to meet customer needs and make money in the longevity economy, businesses will need to address the needs and wants of older (female) consumers. Older workers and entrepreneurs will prove to be an asset in understanding this burgeoning market.

Opportunities

Business mindsets may be slow to change, but opportunities abound.

Cha-ching, cha-ching

The longevity economy presents vast financial opportunities for brands and entrepreneurs who take the time to learn from their aging customers. A report by AARP predicts that by 2030, 52% of US Gross Domestic Product (GDP) will come from money spent by and for adults age 50 and over.

Better life for old and young

In addition to monetary rewards, designing and selling products and services that enhance the lives of older adults can actually improve life for everyone. A new narrative of old age can help younger workers see a path for themselves. A path where they needn’t worry about being relegated to the sidelines when they grow older.

People of all ages can take confidence in knowing they’ll be able to live purposeful, meaningful lives for their whole lives. What’s more, the connections between the generations will enrich the social fabric of our communities.

Some of my best friends are people in their 80s. They may have a few health issues, but by no means are they ready to stop engaging with life in the community. In fact, my friends just might be living with more purpose and intentionality now than they did 20 years ago. I love being around them!

Be the change

Without a doubt, businesses must embrace a new view of old age. Companies that do so will reap financial rewards. Companies that fail to change may not last. The Longevity Economy offers guidance to navigate the transition.

At the same time, each of us has an individual responsibility to change her own attitudes about growing older.

“Be the change you wish to see in the world.” This quote, often attributed to Mahatma Gandhi, urges you to start worldwide change by first changing yourself.

You can continue to dread old age, a time our culture has socialized you to view as bleak, unproductive, and lonely. But at the same time, know that only you can change your mindset.

You can adopt a view of old age that’s purposeful, where you build a legacy of meaning and contribute to the world around you. In doing so, you’ll tap into your own source of joy in aging.

I don’t know about you, but that’s something I want.

Images via: Shutterstock, Public Affairs Books, AHR