When someone has dementia, it’s easy to get frustrated with them. You ask them to do something that (to you) seems simple. But they don’t do it. You wonder if they’re acting obstinate or uncooperative. You try to put yourself in their shoes, but it’s hard.

Good news: both of you will benefit if you part in a facilitated dementia simulation. I recently did one, and here’s what I learned from the experience.

Experiencing dementia improves how you care for someone who has it

Cognitive impairment changes how a person perceives his environment. Dementia simulation helps caregivers appreciate these changes first-hand. You learn how dementia challenges vision, mobility, coordination, and focus.

It’s a brief but profound experience. In nearly every case, undergoing dementia simulation increases your awareness and empathy for people struggling with Alzheimer’s and other dementia-causing conditions.

After as little as five minutes experiencing the world as someone with dementia might, your frustration with dementia-related behaviors can go down. You learn to improve interactions with the person for whom you’re caring. Hopefully, he’ll begin to feel less pressure from you. If things go according to plan, his own level of frustration will decrease as well.

How does a dementia simulation work?

The dementia simulation I did resembles others you might find in your community. Mine was sponsored by ElderConsult, a Bay Area group headed by Elizabeth Landswerk.

ElderConsult focuses on geriatric medicine and education. They offer dementia simulation experiences for free as part of their mission to increase empathy and awareness for this condition affecting over 5.8 million Americans.

Sagebrook Senior Living San Francisco co-sponsored the event. We met at their facility and used two vacant assisted-living suites. There were six of us in our group, although people took individual turns at the simulation experience.

The atmosphere in the group initially felt nervous – no one knew what to expect.

Goggles, shoe pads gloves, headphones

My turn arrived. First they helped me suit up:

- Goggles obscured with hole-punch reinforcement circles that mimicked vision changes a person might have due to macular degeneration, cataracts, etc.

- Shoe pads made from the plastic runners you use to protect heavily-trafficked areas of wall-to-wall carpet. Fortunately, they had filed off the sharpest tips. But still, you put the bumpy sides against your feet to simulate neuropathy and other conditions that make walking uncomfortable

- Medical exam gloves with unpopped popcorn in the fingers to decrease sensitivity and coordination. They taped two fingers together on each hand to reduce my manual dexterity further

- Finally, they gave me headphones that played random, nonstop noises: indistinct voices, machine sounds, traffic, television static

Dementia can feel lonely

Knowing that you had to do the dementia simulation on your own added to your anxiety. In fact, creating a sense of aloneness was one way the facilitators simulated dementia from the outset.

All by yourself in your dementia gear, you felt different. And yet you would be trying to do the same tasks you’d always done – simple things like making the bed, stacking the dishes.

Your facilitator prepped you not to expect contact from her after giving you initial instructions. Thus, no one would be there to help you or reassure you that you were still ok. It felt lonely and a little frightening.

Ready, set, go!

My facilitator led me down the hall to another room. She paused outside and gave me instructions. I would have five minutes to do several tasks. It was hard to concentrate on what she was saying because of the noise coming from my headphones.

Then she opened the door and started her timer.

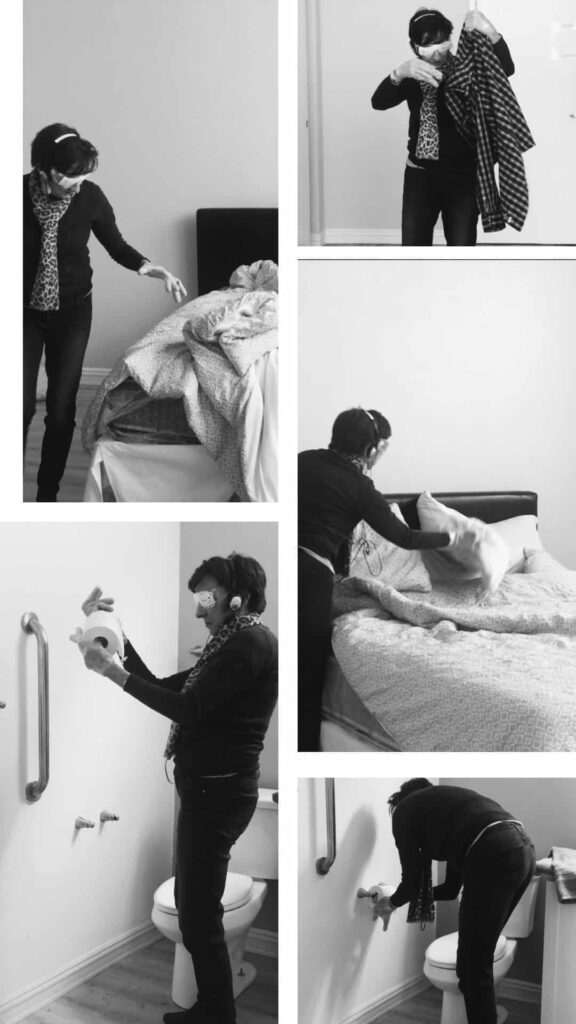

The photo collage shows how I struggled with tasks that otherwise I might find easy.

Bedcovers and pillows

It took a lot of effort to pick up the covers and arrange the bed. I realized I couldn’t make it look nice. That whatever I could do would have to be good enough. I moved on.

Dishes

I worried about tripping as I picked up dishes and put them back on the shelf. I couldn’t see the floor well, and I almost slipped on something small. Even though I knew the dishes were unbreakable, I was afraid I might drop them.

Hanging up clothes

I went crazy trying to hang up a shirt I found lying on a chair. I couldn’t see which part was which, and I couldn’t make my hands hold the hanger and insert it into the sleeve.

Bathroom

By now I just wanted to finish my tasks. The noise in my ears was relentless. I had trouble focusing and felt discouraged. I stopped caring about whether I made the room look good.

I grabbed a couple of towels and threw them over the towel rods. I made no attempt to hang them neatly.

Then I tried to change the toilet paper. I spent a long time on this chore and finally gave up. I couldn’t insert the spring rod into the holes in the part of the TP holder that attached to the wall. My popcorned, taped-up hands were too uncoordinated to do this simple task.

As an aside, I made a mental note that grab bars aren’t the only aspect of making your bathroom age- and dementia-friendly. I resolved to swap out my own paper holders with single post fixtures.

What else?

I was so frustrated when I came out of the bathroom that I couldn’t recall any of the other tasks I was supposed to do. So I just stood there for another 30 seconds or so until time ran out. I emerged tired and defeated when the facilitator informed me my five-minute simulation was over.

Feelings during and after the dementia simulation

The dementia simulation let me experience the frustration that someone with cognitive impairment confronts. Here are specific feelings that contributed to my sense of frustration.

Hard to focus

With the headphones playing random sounds in my ears, and my inability to see my facilitator well through the googles, it was hard to concentrate on her instructions. Her list seemed really long. I knew I wouldn’t be able to do it in only five minutes.

I felt anxious from the start, like I wanted to perform well on a test but couldn’t remember what I was supposed to do. Plus she stood there, silently watching me. I didn’t like having someone watch me fumble through simple chores.

Physical limitations

It was hard to walk with the prickly inserts in my shoes. Plus I couldn’t see, and one time I nearly slipped and fell.

I can’t believe how hard it was to hang up clothes. Lack of manual dexterity, not being able to see which was right side out or where the hole for the sleeve was – all this was super frustrating.

I almost threw the shirt back on the chair. It didn’t seem worth it to hang something up that I might wear again soon. (Now I’m beginning to sound like a teenager!)

Lower standards

In general, I had to lower my standards as I tried to do things like hang up clothes and towels or make the bed. This might not be an issue for everyone, but it was for me.

Relief afterward

My biggest feeling afterward was one of relief. Relief to take the goggles and gloves off, to get rid of the annoying sounds in my ears and prickly pads in my shoes. In essence, I felt relieved to be myself again.

But if you have dementia, you don’t get this relief. You know something isn’t right and long to be yourself again. You wish you could be like you were when you were younger.

For example, you might want to be organized, the way you’ve been all your life until now. Or you might wonder what happened to your coordination, or your ability to knock out a list of simple tasks. Dementia robs you of things you used to take for granted.

With dementia, you might not comprehend that you can’t perform tasks as well as you used to. But still, you have an odd sense of anxiety. You feel diminished, and there’s no escape.

Dementia simulation you can do right now

A in-person dementia simulation gives you a personal experience of what your loved one with dementia may be feeling. But if you can’t attend an in-person event, you still can put yourself into the shoes of a person with cognitive impairment.

ABC News video

Cynthia McFadden, co-anchor of ABC News Nightline in 2012, did a story on a dementia simulation that resembled the one I did with ElderConsult. This 8-minute video goes into detail about her experience. There are some fascinating parallels between clips of a woman with dementia and her son as he does a dementia simulation.

BA Walk Through Dementia

Alzheimer’s Research UK developed a virtual reality dementia simulation that uses the Google Cardboard app. You download their app and use a Google Cardboard virtual reality device (available from Google or Amazon* for $7 to $15) to experience it.

Their website explains why and how they created the app. Even if you don’t have a Google Cardboard viewer, you can experiment with their 360 video clips. Each has a direction arrow that lets you scan up, down and around the environment of the person with dementia.

Here’s a clip that simulates what it’s like for someone with dementia to shop for groceries: