Opioid addiction is widespread in the US: from 1999 to 2019, almost 500,000 people died of opioid overdoses. Some addictions start when recuperating patients receive opioids after surgery. I used opioid prescriptions to combat post-surgical pain after knee replacement in 2020, and getting off opioids turned out to be a major challenge in my recovery.

Here’s my personal account. I hope it may help you or a friend. Feel free to share this post.

Opioids after surgery can lead to long-term use

One hundred million surgical procedures are performed every year in the United States. About half of these are minor, or outpatient surgeries and the other half are major surgeries requiring hospital stays. Research suggests that surgeons prescribe opioid medications to help patients deal with post-surgical pain for 4 out of 5 surgeries, regardless of whether the procedure is minor or major.

According to a meta-analysis of more than 30 studies, 6.9% of people who take opioids after surgery end up taking them for 3 months or longer. Combine this rate with the estimate that opioids are prescribed for 4/5 of surgical patients (80 million people per year). You reach the alarming insight that more than 5.5 million individuals could potentially become persistent opioid users each year, just from having received opioid medication after surgery.

I started taking opioids after surgery and kept on taking them

I almost became one of these habitual users. Someone whom demographers would have classified as an educated midlife female who’d never been exposed to opioids before. I knew opioids were dangerous, but acetaminophen wasn’t enough to relieve my pain. I didn’t know much more than that.

Due to hemophilia, I couldn’t take blood-thinning NSAIDS like ibuprofen or naproxen — so I didn’t have many options for pain relief. At the same time, I didn’t know how quickly I could become dependent on these drugs.

My story: complications after knee surgery

I had partial knee replacements done on both knees in early 2020. After any type of joint replacement surgery, it’s important to avoid blood clots in the leg, or deep vein thrombosis (DVT). To reduce DVT risk, they give you blood-thinning medication.

For me, things got tricky because I have mild hemophilia. Specifically, my blood doesn’t have enough of one of the blood-clotting factors you need to heal well. My surgeon followed all protocols prescribed by my hematologist. Yet, as it turned out, even one dose of blood thinner proved to be more than I needed given my already-thin blood. The incisions oozed and I became anemic.

Thus 5 days after the original surgery, they took me back to the operating room. There the team opened up the incisions and cleaned out a lot of congealed blood. They also inserted little drains in my knees to make sure no more fluids accumulated.

Oxy helped me deal with ongoing pain in the hospital

I spent a total of 10 days in the hospital – much longer than the typical 1-2 stay one has after joint replacement. The second surgery left me in more pain than the first. I was taking long-acting Oxycontin and short-acting Oxycodone, plus acetaminophen. Still, I became anxious and irritable when nurses weren’t there with my meds at the precise time they were due.

I continued taking opioids after discharge

The trauma of the two surgeries left me stiff and unable to get comfortable. I started physical therapy (PT) within a couple of weeks, and that was extremely painful. PT is critical to knee replacement recovery: the therapist has to push you past your comfort zone if you’re to regain your range of motion. This requires encouragement as well as painful manipulation.

When you’re doing physical therapy after knee replacement, you have to bend the knees more than you want to. I took an Oxycodone pill before PT so I could work as hard as possible in my sessions.

Another procedure, more pain

Despite my efforts, I wasn’t making much progress in physical therapy. My surgeon judged that my problems were due to the trauma and scarring my knees experienced in the double surgeries. He recommended that we do one more procedure: Manipulation Under Anesthesia (MUA). This surgery involved no cutting and took about 15 minutes. In essence, MUA works like this: they put you under and then bend up your legs more than you could tolerate if conscious.

The procedure breaks up scar tissue and helps you start moving better when combined with ongoing physical therapy. For me, the MUA was key to my regaining range of motion. But it also left me with lingering pain — not just from the MUA but also from the aggressive physical therapy I pursued in order to capitalize on my new recovery momentum.

Status at 2 months after surgery: still taking opioids

Within a few weeks, I was moving much better but still taking the same amount of Oxycontin and Oxycodone. I weaned myself off Oxycontin, the long-acting version of the drug, as a first step toward getting off opioids after surgery. But it wasn’t much of a step.

Stopping Oxycontin wasn’t hard because I was taking it only a couple of times per day. But I was taking 2 Oxycodone pills every 4 hours. This amounts to 90 MMEs, or Morphine Milligram Equivalents. MMEs are a type of common denominator used to compare different opioid drug dosages.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), daily usage of 50 MMEs or more is high usage. So without knowing it, I’d become a substantial user of opioids. Like others in this category, I experienced physical and psychological side effects.

Physical side effects of opioids after surgery

Although I didn’t understand it until later, I’d become opioid tolerant. As defined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), tolerance ensues when a patient has been taking 30 mg of oxycodone per day (or its equivalent) for a week or more.

I was taking 4 times this amount. Most likely my pain was declining as I recovered from surgery. At the same time, the pain-relieving effect of my medication was also going down. The bottom line: I was on way too much narcotic medication, and I’d been taking it for so long that it wasn’t giving me the pain relief it’d offered earlier.

Understanding the phenomenon of opioid tolerance helped me see how drug use can lead to drug abuse. It would be easy to seek higher and higher dosages, and the possible end result might be an unintended overdose.

A chilling aspect of opioid prescription involves the Naloxone medication that pharmacies dispense alongside the narcotics. If administered in time, Naloxone can potentially reverse the effects of an opioid overdose. I’m glad they include this medication alongside a new opioid prescription: receiving it is a grim reminder to use the drugs with care.

In addition to opioid tolerance and its accompanying dangers, other physical symptoms I experienced were:

- Brain fog: confusion, drowsiness, not feeling “sharp”

- Constipation: this is real – don’t let anyone tell you it’s not. Laxatives help somewhat but not 100%

Psychological side effects of opioids after surgery

I’m grateful for my husband’s support throughout this ordeal. He offered gentle observations that I seemed to be developing a psychological dependence on the drugs. For example:

- Fear of the pain, especially when I’d go to bed at night

- Anxiety over getting my refills before I ran out of pills

Because opioid-dispensing guidelines limited my doctor’s office to less than a week’s worth of pills per prescription, I had to request prescription renewals every few days. It would drive me crazy not to hear back from the physician’s assistant.

Weekends were especially tough if I knew I would be running out of Oxy on the following Monday. I’d make sure to request a refill by Friday, but the doctor’s office didn’t always get back to me before they closed for the weekend. At times my anxiety mounted to near obsession. It took me months to release the negative feelings I held toward the physician assistant who, through no fault of his own, had to monitor my refills.

Feeling trapped

I knew I needed to get off opioids, but I wasn’t sure how. My surgeon offered general guidance that I should reduce dosage slowly, like 10% per week. He referred me to a pain specialist for more specific guidance. Unfortunately, that doctor had no time to see me. I guess he was attending to “real addicts,” or so I told myself.

Pain specialists are in short supply

Surgeons do surgery and prescribe opioids to help you recover. Most of their patients take strong pain medication for just a few days. The surgeon’s job is doing excellent surgery, not counseling the rare patient who has trouble tapering off opioid pills. But M.D.s with pain management expertise are in short supply.

The Association of American Medical Colleges reported that in 2019, general surgeons and orthopedic surgeons numbered 38,000, or 6.1% of all active US M.D.s. Pain management specialists, in contrast, numbered just over 3700, or 0.6% of all specialties. Not surprisingly, median salaries for surgeons were $400,000 to $500,000, while the median pain doctor earned $354,000. Still, a pain physician earned more than the median internist ($225,000, 10% of US M.D.s).

Reasons for the shortage of pain specialists are unclear. But the US opioid epidemic suggests we need many more of them than we have at present.

Opioid usage is private and shameful

My dependence on opioids after surgery was mostly a private matter. Perhaps this was due to the Covid shutdown, when I lost touch with many of my friends. But I believe it was also due to the shame involved in taking narcotic medication. The net result was that I didn’t feel comfortable sharing my situation with friends.

An in-person gathering confirmed this feeling. I declined a glass of wine, saying that I was still taking too many opioids to drink alcohol. A friend joked that I was becoming one of those people. I know she meant no harm, but it didn’t strike me as particularly funny. I decided to keep my narcotic use to myself, at least among this group.

The problem, however, is that privacy can lead to secrecy. Without a trusted confidant or community to support you, opioid pain relievers can lead to opioid addiction.

My decision to get off opioids after surgery

At about 2.5 months after surgery, I resolved to get off the drugs. Since I wasn’t able to consult with a pain doctor, I turned to the Internet for guidance. Specifically, I found information online on how to taper one’s usage in a gradual and safe manner. This was really no different than the instructions my surgeon had offered, to reduce about 10% a week. But it helped me draw up a schedule.

My opioid taper action plan

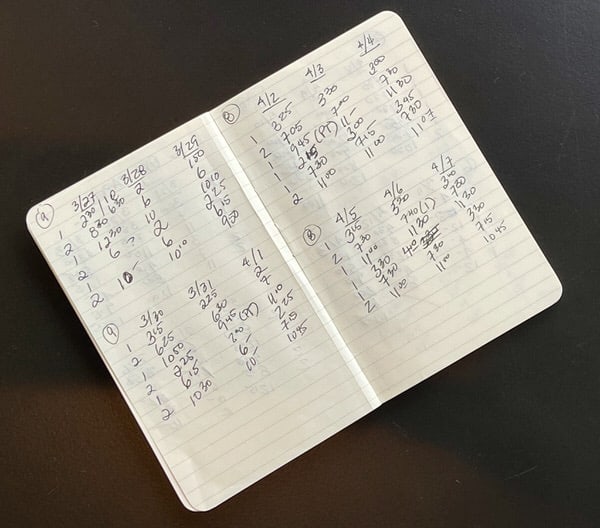

I mapped out my taper schedule in a notebook and put it beside my bottle of pills. Starting at a high of 12 pills per day, I went down to 11 pills per day for the first three days, then 10 pills per day for days 4-6, then 9, then 8, and so on. I made sure to cut the evening dosage after reducing all other doses that day. This was to increase my chances of sleeping at night.

Here are the actions that helped me get off opioids:

- Taper schedule

- Support and accountability given by my husband, who never judged me but helped me achieve my goal

- Regular deep tissue massage by a trusted practitioner with experience treating joint recovery patients

- A topical CBD cream that I used throughout the day and night as needed

- Regular exercise in addition to physical therapy

- Sunshine, good food and other things to boost my mood

Opioid withdrawal symptoms

Withdrawal symptoms are both physical and psychological. You can find comprehensive lists of opioid withdrawal symptoms online, but these were the ones I experienced:

- Shivering: I would get in bed at night and start to shiver, even though I wasn’t cold. Sometimes I had the shivers so bad that I just got out of bed and walked around until they stopped. I didn’t know this was a withdrawal symptom until it had been going on for over a month

- Diarrhea

- Insomnia

- Anxiety: my husband’s reassurance really helped here

A few months later, I was finally able to consult with a pain specialist. Although most of my withdrawal symptoms had subsided by then, he prescribed Clonidine, a drug originally developed for high blood pressure that can help reduce narcotic withdrawal symptoms. This would have been a good medication to know about earlier!

Relief at tapering off opioids after surgery

I took my last Oxycodone about 6 weeks after starting to taper my usage. It gave me an enormous sense of relief and accomplishment. Most people in my social circle don’t really understand how significant this achievement was for me. For the most part, opioid use is something that happens in private.

Now I’m highly reluctant ever to take opioid medication again. I certainly won’t take narcotics for chronic pain, as I’m concerned about building up a tolerance that renders the medication ineffective. I’m not sure how I’ll deal with acute pain such as post-surgical pain. But I’m hoping to have more input on my options if I ever need major surgery again. I’ll certainly know more than I did last time.

You can get off opioids after surgery

I’ve shared my story so you won’t feel alone. Opioid addiction has many faces. You might be surprised to learn of people in your midst who use or abuse prescription drugs.

Your job is to reach out before it’s too late. Get the facts. Find an accountability partner, a pain specialist, a support group. You don’t have to become one of those people.

If you or someone you know is suffering from substance abuse, confidential help and referrals from government agencies are available:

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

1-800-662-HELP (4357)